clear up your patients’ confusion about which masks work best

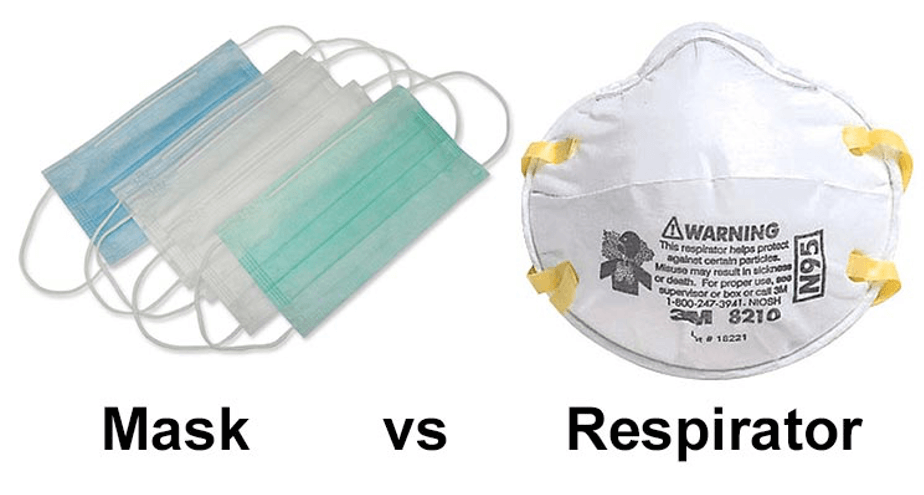

The emergence of the quickly spreading COVID-19 Omicron variant has patients wondering what kind of mask they should be wearing, particularly when in public indoor spaces. As knowledge of masks and their benefits continue to evolve, physicians want patients to know what to look for when choosing one to wear. In April 2020, the first recommendation for mask-wearing was to protect others—your family, friends, and the older adult or immunocompromised person at the grocery store. Now, though, the growing body of evidence suggests that wearing a mask to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2—the virus that causes COVID-19—is key to protecting yourself too, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). “The science is really clear on this—masks are an important way that we can all slow down and prevent the spread of COVID-19,” said Preeti Malani, MD, chief health officer and professor of medicine in the infectious diseases division at the University of Michigan. Dr. Malani is also associate editor of JAMA. It’s essential to practice physical distancing and avoid gatherings, “but basically anytime you’re with anyone not in your immediate household or in any public space when you’ve left your house, we should be wearing a mask,” said Dr. Malani. “It should be part of our uniform, like you would wear shoes.” “It’s just become something that people have gotten used to. At the same time, there are people who don’t want to wear masks and science is not necessarily guiding that, though,” she said, adding that the science is clear on this—masks are an important tool, along with vaccines, to help stop the spread of COVID-19. Because SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted predominantly by respiratory droplets and aerosol particles generated when people talk, breathe, sneeze or cough, the CDC recommends community use of masks. With this guidance from the CDC, Dr. Malani offered advice on choosing the right mask to stop the spread of COVID-19. Think about double masking At a minimum, people should consider wearing two masks—or double masking—while Omicron and Delta variants continue to spread. This means wearing a cloth mask over a surgical mask for a tighter fit. A mask fitter can also help improve the fit of a person’s mask for better protection. Adding more layers of material to a mask—or wearing two masks—reduces the number of respiratory droplets containing the virus that come through the mask. If one person is using a cloth mask over a surgical mask while the other person is not, it has been shown to block 85.4% of particles emitted during a cough. While double masking or a mask fitter may not offer as much protection as an N95 respirator, they are a big improvement compared to a cloth mask alone. Masks that fit properly When choosing a mask, ensure that it fits properly. That means it is snug around the nose and chin without large gaps around the sides of the face. The mask should be comfortable Wear it consistently and make sure it covers your mouth and nose completely Avoid ill-fitting masks such as spandex neck gaiters, which “don’t stay in place for most people, Multilayer, tightly woven cloth masks The use of multilayer cloth masks can block 50–70% of fine droplets and particles. They can also limit the forward spread of droplets and particles that are not captured, notes the CDC. In fact, upwards of 80% blockage has been achieved with cloth masks in some studies, which is about on par with surgical masks as barriers for source control. Other materials, such as silk masks, may help repel moist droplets. They may also reduce fabric wetting, which can help maintain breathability and comfort for the wearer Posted By Author Sara Berg, MS AMA Affiliated Groups Senior News Writer

Articles

Most Popular

some seemingly minor symptoms that could be something major and need to be checked by a physician asap

The following are some symptoms because of thats are likely to be in big time trouble.

(Note : These may be innocuous symptoms too, but they ring an alarm in a physician’s mind, an alarm that cannot be put into a snooze mode till a problem is ruled out )

1. Feeling of tightness, stiffness or pain in lower jaw – Sign of Heart disease

2. Transient double vision, slurred speech – Early stroke

3. Difficulty in swallowing – food getting stuck – Mass in the esophagus

4. Painless ‘red’ pee, ‘black’ poo - denotes internal bleeding.

5. Change of voice, hoarse voice, in the absence of ‘cold’ – check the voice box.

6. Any new ‘hard’ swelling - Make sure it is not the ‘emperor of all maladies’

7. Sitting up at night because of breathing difficulty – Heart Disease

Experiencing similar type of symptoms? Or for Online consultations Call on

+91-87 930 930 20

In Contrast

Symptoms that make you run to a doctor but the doctor is all smiles.

1. Most chest pains that you can point and localize with one finger – Non-cardiac

2. Need to take intermittent deep breath - Anxiety

3. Giddiness and nausea on head turning – Benign positional vertigo

there are more viruses than stars in the universe. why do only some infect us?

More than a quadrillion quadrillion individual viruses exist on Earth, but most are not poised to hop into humans. Can we find the ones that are?

An estimated 10 nonillion (10 to the 31st power) individual viruses exist on our planet—enough to assign one to every star in the universe 100 million times over.

Viruses infiltrate every aspect of our natural world, seething in seawater, drifting through the atmosphere, and lurking in miniscule motes of soil. Generally considered non-living entities, these pathogens can only replicate with the help of a host, and they are capable of hijacking organisms from every branch of the tree of life—including a multitude of human cells.

Yet, most of the time, our species manages to live in this virus-filled world relatively free of illness. The reason has less to do with the human body’s resilience to disease than the biological quirks of viruses themselves, says Sara Sawyer, a virologist and disease ecologist at the University of Colorado Boulder. These pathogens are extraordinarily picky about the cells they infect, and only an infinitesimally small fraction of the viruses that surround us actually pose any threat to humans.

Still, as the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic clearly demonstrates, outbreaks of new human viruses do happen—and they aren’t as unexpected as they might seem.

To better forecast and prevent outbreaks, scientists are homing in on the traits that may explain why some viruses, and not others, can make the hop into humans. Some mutate more frequently, perhaps easing their spread into new hosts, while others are helped along by human encounters with animals that provide opportunities to jump species.

When it comes to epidemics, “there are actually patterns there,” says Raina Plowright, a disease ecologist at Montana State University. “And they are predictable patterns.”

Crossing the species divide

Most new infectious illnesses enter the human population the same way COVID-19 did: as a zoonosis, or a disease that infects people by way of an animal. Mammals and birds alone are thought to host about 1.7 million undiscovered types of viruses—a number that has spurred scientists around the world to survey Earth’s wildlife for the cause of our species’ next pandemic. (Bacteria, fungi, and parasites can also pass from animals to people, but these pathogens can typically reproduce without infecting hosts, and many viruses are better equipped to cross species.)

To make a successful transition from one species to another, a virus must clear a series of biological hurdles. The pathogen has to exit one animal and come into contact with another, then establish an infection in the second host, says Jemma Geoghegan, a virologist at Macquarie University. This is known as a spillover event. After the virus has set up shop in a new host, it then needs to spread to other members of that species.

Exact numbers are hard to estimate, but the vast majority of animal-to-human spillovers likely result in dead-end infections that never progress past the first individual. For a new virus to actually spark an outbreak, “so many factors need to align,” says Dorothy Tovar, a virologist and disease ecologist at Stanford University.

For a virus, one of most challenging aspects of transmission is gaining entry to a new host’s cells, which contain the molecular machinery that these pathogens need to replicate. This process typically involves a virus latching on to a molecule that studs the outside of a human cell—a bit like a key clicking into a lock. The better the fit, the more likely the pathogen is to access the cell’s interior. SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, engages with the protein ACE2 to enter cells in the human airway.

For any given host, “there’s a very small number of pathogens that are able to” break into its cells this way, Sawyer says. The vast majority of the viruses we encounter simply bounce off our cells, eventually exiting our bodies as harmless visitors.

Source: Nationalgeographic

Score

Score